As I played The Ascent, I kept getting reminded it was built by a mere twenty two hands. The fact a game this visually stunning was even possible blows my mind. The build up to The Ascent made me remember this fact too, the vocal anticipation for it felt similar to the rowdiness a big AAA release garners, not an indie gig forged by eleven people. And then I started playing it, basking in one of the first worlds which truly looked next-gen, admiring the liviness brewing inside The Ascent’s tawdry cyberpunk world.

And I played it some more, and some more, and some more, until I eventually completed it. And here I am, plonked down writing a review on it, and I can’t help but feel somewhat mournful that I’m tasked at explaining why a title brimming with such gaudy beauty developed by a small, passionate team resulted in such a disappointing hodgepodge of a game.

A lowly, silent, slave on the world of Veles takes the lead as our player protagonist. We’re afforded no time to bask in the planet’s luxuries, and we’re sent into the “deepStink”, the lowest arcology level, tasked with fixing the area’s artificial intelligence, employed to keep the shit from rising into the habitats above. Quickly we’re introduced to way too many concepts, names and locations, inundating the player with phrases you’ll either forget or never know the meaning of, but equally as rapidly we’re able to start shooting at some baddies, and suddenly everything isn’t so bad.

It’s difficult to know where to start with The Ascent, because discussing one element impels me to discuss how it relates to another in an inorganic, rambly kind of way. Let’s start with Veles, a cyberpunk world indisputably. I’m not a connoisseur of the aesthetic, but I know some staples, and all of them pop up in The Ascent. Western world twinned with Asian culture, pronounced neon lights suffused over a mechanical and technological underbelly. Derivative, but ultimately benign if executed properly, and The Ascent does so beautifully. So garish and blinding, yet so shiny and polished. Reflections on puddles and on the sparkly exterior metals look gooey and palpable. It’s all rendered with such fidelity that I obstinately refused to believe eleven people made it – of which assuredly a fraction of that small number actually handled the art. Furthermore, playing on a Series X, my playthrough was supposedly “gimped”, lacking the ray tracing of the PC version. It makes you wonder how eye-wateringly immense it must look there, if it looks so blissful here.

It doesn’t stop at textures either. Veles looks lived in, bustling streets and open platforms are rammed with fellow indentured citizens (“indents” as the game calls them), crammed together like a fitting dystopian canvas. Clubs and shops exhibit scenes of exultation and dodgy activity, occasionally shrouded by the glare of neon flashing lights. Appearance wise, it’s spot on, but it serves no gameplay purpose. I wasn’t particularly miffed about it, as The Ascent never plays like a proper RPG, whereby dense dialogue and character relationships need to be facilitated. There is a verisimilitude about Veles despite functional shallowness, and I just accepted to appreciate the environments for the tone setters they were, and I was happy to be part of the world Neon Giant have created, if only as a spectator.

Despite The Ascent’s instantaneous pangs of quality in the art department, it takes time for other areas to fully realise, one of which being the combat. The Ascent is essentially a top down shooter with some light looter elements. Veles is left slightly ajar, peeping inside we see a handful of levels to climb up and down, and each level vaguely depicts a different class structure, segmented into different zones inside each sector. The starting level, deepStink, distinctly looks vile, with a yellow veil hung over everything, surrounded by tatty mechanics and a blatant lack of organic life. In the deepStink, we fight some entry level plebs, but the game does a decent job explaining its mechanics, which fundamentally boil down to tight top down shooter controls with an added height system, where you can shoot high or low depending on the enemy, your height and what you intend effect you intend to inflict.

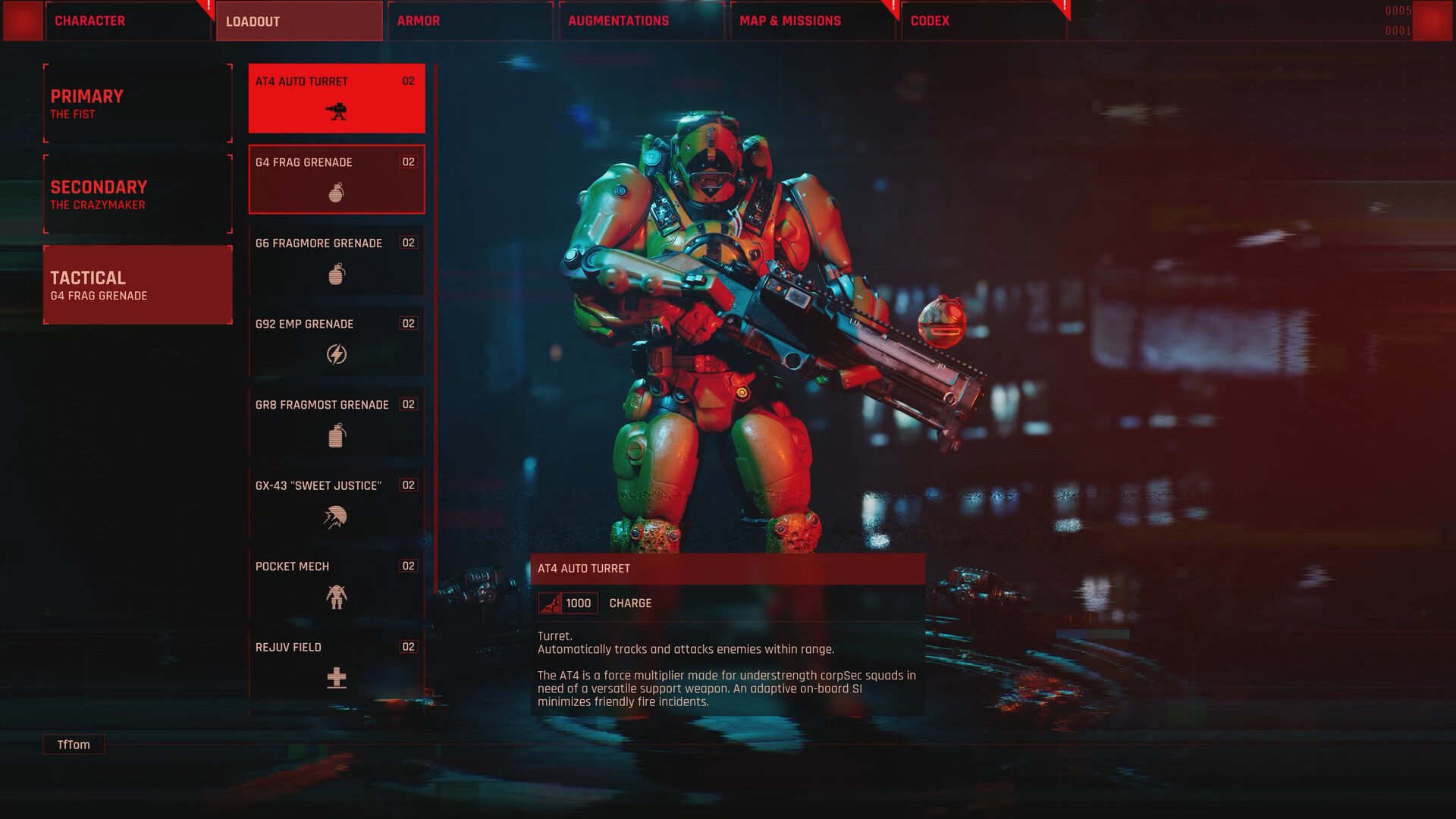

I enjoyed The Ascent’s core gameplay, even in spite of how long it takes for it to truly rev into a lively pace. Part of that is due to the novel aiming mechanic. Aiming high will concuss enemies more, leading to a stagger effect quicker, while aiming low ensures you’ll hit every enemy in the general vicinity even if they duck or exist as a halfling feral. To play into this, The Ascent’s environments scatter cover positions liberally across the world, allowing you to jump behind a car, and spray bullets above your head. You also learn abilities which charge as you deal damage – most of which are grenades but some turrets and niche stun utilities exist too – further acquiring separate abilities which drain an energy meter which recharges over time. Combining all of them, there can exist some interesting fights, ones where you’re swarmed with melee goons and you blast a bike with a low shot to have it explode in their faces, ones with foes spraying you from afar with assault rifles, for you to activate your “slow time” ability and get right up in their face. Ten hours in and The Ascent really hits its stride, as you have enough build diversity, energy and formidable enemies to forge engaging combat scenarios. Yes, it takes time to get to that point, but in full swing The Ascent is a borderline routine top down shooter, executed as well as the best.

Time. Time is the key here. It takes time to get to that point, but after some time it starts to wear a bit thin. It takes time to get anywhere, and I don’t have the time to read endless logs explaining the minutiae which makes up this game’s lore. It’s a shame too as I think somewhere exists a genuinely intriguing world, but understanding it takes time and effort, as The Ascent makes attaining that knowledge a prosaic and woefully inefficient process. Broadly speaking, the plot of The Ascent has you carry out tasks for your masters, changing hands occasionally between characters I’ve already forgotten the name of. Poone. I remember Poone, and I think that’s purely because his name is British slang for something I immaturely found funny. One of the menu options contains a codex, positively packed with details on everything you could possibly want to know about Veles, its inhabitants and the systems it’s built on. I’m impressed by the vastness of the compendium, but less so with how it’s almost the sole source of information, as cutscenes are sporadic and dialogue is a complete mess. From the first utterance of speech, The Ascent is overwhelming in how much exposition it throws at the player. Complete unremorsefully, attempting to kindle a connection with the player after every information dump through dialogue options entirely consisting of questions about whatever nonsense the NPC just spoke about. After the first few interactions, I gave up trying to decipher The Ascent’s concepts, as it’s not told in an engaging fashion at all. SI, AGI, Imprinting, ICE, Menshen. These are words. Words I don’t know the meaning of, and they’re spoken to the player like they’re elementary school English. I want to learn about Veles and the hokey, corrupt behaviours fueling it, but it’s like The Ascent doesn’t want me to.

Let’s say we haven’t hit that plateau yet though. We’re not ten hours in, we’re still getting to grips with our life as a pitiful indent and our arsenal is lacking. Is the game still fun? Partly. Early in, I was carried by the liveliness of the habitats and simplicity of the combat, but signs of bloat are visible. Part of that is in service to the exposition dumps just mentioned – or rather the laborious time you’ll have to spend reading plain text from your codex or in-game logs to piece together the narrative and lore. However, a more substantial instance comes in the form of navigation, in a few senses. In terms of bloat, The Ascent never felt destined for the semi-open world design it utilises. Put simply, moving from one area to another is monotonous, inefficient and feels intentionally onerous in the name of padding out the game’s overall length. I don’t say that lightly, nor do I say it with definitive proof either. Malicious design was hopefully not the intent here, but it certainly feels oppressive and cuts into your overall time spent deeply. There’s no effective means of fast travel in The Ascent. The greatest form of transport we’re afforded initially appears with the train system, designated sections on a level which will zip you around between each one, usually five or so. I detest the goddamn train. Not only does the travel cutscene take way too long for the supposedly alien SSD technology of the Series X, but the stations are situated is utterly stupid positions, often a few hundred meters out of reach of where you actually want to be, which amounts to a few more minutes of walking on foot, or rather using your dodge ability because it looks faster (no idea if it actually is). Sometimes I’d bank on my ability to just walk to an objective quicker, although both means of travel take an extraneous amount of time and fixate in my mind as a core principle of The Ascent’s design, which given how mundane they are, I’m not pleased it will have a lasting effect on my memory of the game.

There was another aspect to navigation I found myself disappointed with however, and that’s the ironic lack of ascending present. I found myself relating back to ACE Team’s A Deadly Tower of Monsters, a game which had us climb the titular pernicious spire and one which had an unrivalled sense of verticality, emphasised most by the game’s vertical combat sections which had us aim over the sides of the tower and blast ascending enemies. You truly could see your progress, picking out landmarks below despite the great heights you’ve climbed. The Ascent’s namesake evidently alludes to the societal pilgrimage of the plot and common class war tropes found in the cyberpunk space, but it’s strange barely any of that translates into the game’s mechanics. There are bits and pieces of verticality; sometimes the camera will pan into different angles, flaunting it’s awe inspiring visuals and giving you a glimpse on the life below, and as previously mentioned, deciding whether to shoot high or low adds depth in the combat department. But it’s transitory, or at the very least not prominent enough, never feeling as deep (literally) as I thought it would have given the obvious structure of Veles. The in-game map goes so far as to actively discourage the notion a game called The Ascent is about journeying upwards, exhibiting very little depth and making navigation as a whole quite confusing. At the end of the day, only four or so levels exist in this arcology, one of which you only enter in the final few missions. In many ways The Ascent feels at odds with itself – with the open-ended map drawing attention away from the narrative and the energy system limiting how often you can use the fun abilities – but it’s no more highlighted than with the total hypocrisy found in the game’s title.

Something I never typically delve into with my reviews – on the grounds of typically playing games years after their initial release – is the state it’s in, how buggy or, hopefully, stable it is. The Ascent is stable in the sense it functions without crashes, nothing is truly game breaking, but it’s evident the game suffers with niggles here and there. To be fair, it’s another game which the Series X’s revolutionary yet fundamentally inconsistent “Quick Launch” feature conflicts with, making the game feel even buggier than it really is, notably causing audio to loop in a din of ear shattering, twisted gunshots. Excluding that – by which I mean I ensured I played the game without Quick Launch – The Ascent still breaks immersion and tests my patience with bugs including chests not opening for any good reason, or my weapon disappearing mid fight, reappearing a second before I die as if in sinister taunt. They’re not major, but significant enough I thought it’s worth pointing out, despite my general leniency for stuff like this.

When it comes down to it, The Ascent’s at its worst when it’s trying to be a looter shooter, and at its best when it revels in its own technological achievements. Voice acting across the board is decent, but characters like nogHead and your IMP (the Alexa of the future) really imbue the game with some much needed charm and wit, especially so with your IMP, an intangible maniac perpetually commenting on their adoration for your senseless destruction. She brought a few laughs to the table, as did nogHead’s quick witted retorts and low attention dialogue pieces. Unfortunately, these parts are rare, and what I truly loved about the game in its gorgeous world design and meaty combat gets muddied by perpetually dull loot, dogged fetch quests and areas five times as big as they needed to be, seemingly to inflate the playtime by the same multiplier.

There’s no “saving” The Ascent, despite the short paragraph on the egregious bugs, because it’s flawed at its core in my opinion. It’s a game which feels unsure about itself, too unconfident to drop to a mere two to three hour long experience and instead throws in redundant mechanics from a game which this shouldn’t be. Because The Ascent, with the incessant loot and mundane side quests shoveled out the way, is a truly next generation release technologically, one which feels touched with love and affection in a way which a glorified tech demo like Ryse or Killzone never achieve. In the same way, it’s a game which takes standard top down shooter mechanics, alters them slightly, and does a wonderful job of making it play strikingly well; the classic “what’s old is new again”. The Ascent is far from terrible, but unfortunately the road towards greatness is just as far, one leading towards a mountain, which it obstinately refuses to climb.