Is there truly anything better than the 1993 gun-blazing progenitor Doom? No? Alright, see you in the next one.

When I first played Doom five or six years ago, it changed something in me. That might sound melodramatic – we are talking about a game in which you spank demons with literal, Big Fucking Guns after all – but it’s true, it altered my perspective of video games as a medium. Growing up, my tastes were impressively varied, at least going by the homogeneous routine of Fortnite and Roblox I see lots of kids settle into nowadays. Perhaps I was even more adventurous then than I am now, dipping my tootsies into genres like RTS, which I now avoid out of the inevitable misery I’ll experience when I realise I’m still terrible at them. I leaped between my lushious, verdant gardens in Viva Pinata to the slippery, snowy peaks of Super Mario 64, hopping into Disney’s Extreme Skate Adventure for some PG angst and finished my day fluttering between the large, varied and free library of games on funnygames.biz.

But I also played a lot of Call of Duty. Every kid did. Maybe I was a homogeneous kid after all. Weirdly, despite the whimsical restiveness I’d have for trying new games in every genre known to man, first person shooters wasn’t one of them. Call of Duty might as well have been the name of the genre for all I knew, as it was the only one I ever bothered to play, and I ended up playing it a lot. The vast majority of that playtime was most definitely online, partly because the offline bored the hell out of me, but it was also the Fortnite of my generation, and even if you didn’t enjoy it, you played it because it was “in”.

It’s a shame really, because for the longest time, Call of Duty’s endless corridors, two-weapon limit and braindead AI was what I correlated with offline shooters, it was all I had experience with. Therefore, the unholy blaze of light Doom emitted merely needed to glint in my general direction to entice me, but I had no idea about the beast that was going to completely envelop me.

In a way, I’m quite glad I experienced Call of Duty as much as I did, as the delta in quality between Doom’s dastardly campaign and the maligned monotony Activision were pumping out every year only opened my eyes further into what an exceptional video game can be. For me, Doom was a bastion of game design, while Call of Duty epitomised everything I hated. Doom had levels which somehow managed to retain a small footprint, yet felt expansive and winding. It’s extensive arsenal whereby each weapon is a button away from operation, ready to suit the current situation. It’s enemies, designed to match and test your abilities rather than merely emulate moving cardboard targets. Everything about Doom is a long-explored, revered piece of video game magic. It’s one I can’t even come close to doing justice in writing, but, ultimately, it’s a video game I want to express my unabashed, indebted love for.

Providing a backdrop for this review almost seems as pointless as giving a summary of what Sonic The Hedgehog is about: they’re classics ingrained in not only video game culture, but pop culture as a wider phenomenon. Released in 1993 by id Software, Doom was one of the first of its kind, initially forming a genre known as “Doom-clone”, which eventually went by “first-person shooter”. There were releases before Doom – id’s very own Hovertank 3D, Catacomb 3-D and Wolfenstein 3D predated it by a couple of years alone – but Doom was a game larger than life, so immensely innovative it made prior attempts at first-person pseudo 3D shooting appear archaic and obsolete. It took the general concept, and launched it to a level never seen before.

“Seen” actually being key here, as Doom utilised the pioneering “id Tech 1” engine, birthed to necessitate the complex rendering used in Doom to fake its 3D world. Yes, Doom isn’t truly 3D, but it does a convincing job with its mirage. In comparison to its predecessor Wolfenstein 3D, Doom looks like it’s from another era, combining advanced wall and floor geometry along with a more nuanced lighting system to give depth to the hellish world they created. It is nice, especially in contrast to the flavourless levels games ran with before it, although some of the constraints in level of detail possible do still stick out slightly. At the end of the day though, I believe Doom’s look has aged nicely, and like many first-person shooters of that approximate era, lighting played a key role in setting the unsettling tone games like Unreal, Quake and, of course Doom execute so well.

Before going any further, it seems thoughtless in 2021 to not mention “source ports”. Source ports are self explanatory to a degree, adaptations of the source code released a few years after Doom first blessed our souls. They initially existed for cross-platform unity, but nowadays, they are essential tools for playing the game (and many others) on modern systems. Purchase the game anywhere, console or PC, and you’ll be playing Doom, in some fashion, through a source port, due to the fact the game was originally released on the antiquated MS-DOS operating system. It’s an important topic to talk about when discussing playing Doom, because each source port exists for different reasons. I first played Doom through perhaps the most popular PC source port, GZDoom. As a source port, it seems to serve a jack of all trades, offering functions and features the original version of Doom didn’t have, yet being modular enough to allow you to customise it in a way which is still faithful to the original, in addition to substantial modding support. On my most recent playthrough, I played the game through a source port called Chocolate Doom, a play on the word vanilla which, as you can imagine, tries to replicate the seminal 1993 release boringly accurately.

Now, having played the game through both, is there a source port I’d recommend ahead of another? If you’re trying to achieve an authentic experience, not really. Although Chocolate Doom is fantastic at what it does and gets recommended plenty for being a faithful source port, GZDoom can essentially do the same, although the former’s uncomplicatedness earns it points too. The problem I have with GZDoom is that out of the box, it is evidently tailored towards a heavily modified reproduction of Doom which absolutely isn’t faithful, higher textures and mouselook enabled from the offset to list two changes which conflict with potential aspirations of authenticity. That said, it’s friendlier. Chocolate Doom, even digging into the simple options menu, does look a bit ancient and looks ready to bite your hand off if you press a button the wrong way, whereas GZDoom is crystal clear and easily navigable with the mouse alone. Ultimately though, GZDoom does have some features which, while not wholly authentic, can better your experience with the game. Simply put, Doom in its original form does carry with it baggage of that time, low resolution textures namely which makes looking at enemies from a distance a bit weary on the eyes. It’s a topic worthy of lengthy discussion, but for now, know that it’s something which can and will affect your experience with the game.

Jumping into the game – which for reference I’m reviewing through Chocolate Doom’s nostalgia goggles – Doom proves refreshingly uncomplicated. When Doom 2016 released, many people were quick to praise it for it’s no nonsense approach to story, by that I mean it considered stories nonsense and ripped and tore it’s way through the potential plot’s guts right to the action. It’s antecedent shares the same approach, uttering not a single whisper of narrative until a single slide of text at the end of each episode. Doom is split into three episodes by the way, eventually four with the release of The Ultimate Doom named Thy Flesh Consumed. The vast majority of this review excludes the supplementary episode, as it’s something…different.

You spawn into the first episode, Knee-Deep into the Dead, with nothing but your fists and a pistol. New players might be shocked to find you play as a vertically-impaired demon slayer, but it’s true, Doom in its classic form had no option to look freely up and down, and believe it or not, you do in fact slay demons. Personally, I enjoy what is, fundamentally, an engine limitation. Looking up and down isn’t a luxury afforded to the player, but you promptly forget about it thanks to Doom’s implementation of aim assist. You can use either the keyboard or mouse to look left and right, and any enemy on the Y axis which enters the centre portion of your view is automatically targeted as if you were aiming at them directly with a crosshair. I don’t prefer it, per say, but it’s a pragmatic resolution which allows the player to focus on other things outside of aim. I can speak from experience that plenty of shooters, especially online ones, place considerable focus on players aiming with precision (tools like Aimlab are big for reason) and sometimes I feel disconnected from other elements of the game as a result, like how I move or considering whether the weapon I’m using is at all suitable.

Movement and weapon selection are vital in Doom, so that must mean I carefully selected those examples for use as a cheap segway. Fans will often cite Knee-Deep into the Dead as the perfect episode, further acting as the perfect tutorial also. From the very first opening room in mission one, you’ll experience Doom’s woozy speed. Even without running, you move fast in this game, swaying daintily side to side, obverse to the hellish brutality surrounding you. You quickly meet your first foes: the zombieman, imp and shotgun guy. The former foe acts as fodder, only serving as a light annoyance in numbers due to their hitscan weapons which somehow deal less damage than your pistol. Imp’s are the opposite, visually grotesque and physically more vigorous, launching projectile-based fireballs in your direction. Due to their lack of hitscan, you can use the game’s zippy pace to your advantage to evade fireballs and consequently whittle them down without so much as grazing burn on you. Then you move onto the shotgun guy. He wields a devastating missile launcher capable of dropping you with one shot in a terrible mess of explosives. Not really, but the shotguns they use are scary, even more so when you tear them from their corpses and use them against their brethren. The shotgun is the first real step into what makes Doom’s gunplay great, and that’s the raw weight weapons have behind them. Often overshadowed by its sequel’s double barrelled boomstick, the shotgun remains consistently useful, having significant heft to match its impressive damage output. Every gun in the game is like this. The advanced peashooter (also known as the chaingun) lacks the instantaneous oomph from the shotgun blast, but the rapid cycling of bullets feels weighty in its own way. The rocket launcher doesn’t need any explanation in the way of it being a rocket launcher, but Doom executes it doubly well by complementing the release of rockets with a gusty “woosh”, along with some assertive pushback on enemies when they land. The “literal Big Fucking Gun” I mentioned in the intro is more of the same, raining down colossal damage on hit, chaining from enemy to enemy and feeling like a huge release of energy.

That’s the first thing you notice though, as similar to the dynamic between yourself and the imp, the game’s whirlwind pace makes fighting most enemies in the game a tribal dance of spells and bullets. The cacodemon, baron of hell, cyberdemon and the aforementioned imp all rely on projectiles to deal the bulk of their damage, thus creating this brilliant combat loop whereby just as much emphasis is placed on your movement than it is your raw damage output. Oftentimes, even with a puny starter arsenal, you’re able to overcome waves of demons just by weaving in and out of them, whittling them down with whatever weapon and meager ammo you have. “Circle Strafing”, the technique by which you move around the opponent quicker than they can fire at you, was popularised (and arguably spawned) by Doom, and due to quirks in the engine, moving in a diagonal trajectory rather than a lateral one boost you even faster. It’s a rapid game, so quick you often forget some enemies are hitscan. One of the first things I noticed when I first played Doom was this idea that enemies shouldn’t lock onto you with absolute accuracy, in fact, as modern military shooters are nothing but hitscan weapons plus grenades. It would be naive to say hitscan is generally worse than projectile-based enemies, but it’s true, in my experience, to claim Doom’s emphasis on the latter makes for a more varied, enjoyable shooter which facilitates skillful, satisfying combat maneuvers.

Let’s talk about the enemies in greater detail, and go on a bit of a tangent while we’re at it. In 1956, George A. Miller of Harvard alumni published a psychology paper centred on the concept of the working memory, and with it a postulation summed up as the “magical number seven, plus or minus two”. To cut to the point, the working memory can only hold so much information, and in Miller’s venerable yet debated paper, he claims we can only hold seven (plus or minus 2) items of information in our short-term memory. Why is this relevant? Doom, minus the two “boss” enemies, rotates between 8 common demons, and by the end of the game you feel like you could write an essay on each of them. They’re memorable, for plenty of reasons outside this theory too, but if Miller’s work bares any truth, it’s not unreasonable to claim the number id Software chose for the amount of enemies makes keeping track of them so easy. If this sounds familiar, it’s because the revered Mark Brown mentions this in his “What Can We Learn From DOOM” video, which for those that haven’t watched it, absolutely should right now. Override this tab and watch it, it’s brilliant.

Like I alluded to though, Doom’s enemy design goes beyond potentially tenuous links to psychology. Each and every one of Doom’s enemies visually pop; easily identifiable and weirdly lovely to look at in their grotesqueness. Again, I don’t want to tread on territory a better critic has already made, but simply put, Doom’s limited pool of enemies makes recognising one from afar in a swift second reaction a thankful design choice. The creepy brown fur which coats the imps are effortlessly contrasted by a pinky’s hulking hunchback appearance, which also sits on the other end of the visual spectrum to the lanky, minotaur-like baron of hell. I appreciated this even more so with my latest playthrough through Chocolate Doom, as Doom in its original form lacks precision when it comes to distant objects, often dissolving into a blurry, scarlet texture. Deftly associating the hazy figure with its corresponding threat level was an essential skill which came naturally thanks to their designs. They are all hideous, fittingly so. Not quite as revolting as Doom 2016’s modern graphics portray, but even still they’re ugly enough to suitably reside in hell. The cacodemon, a massive horned ball of crimson flesh, and the pinky’s tank-like, bullish figure are personal favourites, but even the mutated faces of the zombiemen and shotgun guys add a layer of horror to the world of Doom.

That’s another thing the game does well, atmosphere. I keep saying “hell” like Doom is strictly set there, but two of the three episodes use UAC (Union Aerospace Corporation) bases for backdrops, albeit with a demonic twist, as if they were abandoned and overgrown with ghoulish greenery. Even in its vanilla appearance, Doom’s striking visuals remain a source of terror and fear, although as I claimed before, it can sometimes eer on the side of hazy by today’s standards. The best game to compare Doom to for impact would be id’s prior shot at the shooter formula, Wolfenstein 3D. Themes aside, Wolfenstein 3D levels are unvaried and lifeless, coming nowhere near close enough to evoke the strict disciplinarianism you’d expect from a Nazi stronghold, and even further from having the appearance of a game which isn’t dreary and literally flat. Doom is layered, somewhat precisely too as with id Tech 1, the levels they were capable of making were far more adventurous, diverse and visually entertaining than that of the WW2 era’s eponymous engine. Where Wolfenstein 3D pasted walls with bare, boring blue, Doom’s are textured, differing and build a sinister atmosphere. In the more hellish levels of the third episode “Inferno”, scrolling textures of stretched faces frequently occupy rooms, and there’s something so unsettling about it, they look too human to be in a video game. Some walls look like they’re bleeding, others are coated with natural wood. Disparity alone is a welcome addition coming from Wolfenstein 3D, but the fact it paints such a clear picture of your journey from one location to the next is worthy of praise.

On the topic of presentation comes sound, which again enhances the gameplay and pleases the senses. While on a technical level this game and Mick Gordan’s soundtracks for the latest two Doom games are in opposition, the sentiment and tone is the same. At Hell’s Gate is a video game music icon and it’s the very first track which plays as you start Doom. What an opener! The initial short opening guitar riff gives off this sense of foreboding evil, then the drums clash into the mix and create this blood-pumping tune, contrasting with the helplessness of the opening 10 seconds and gets you ready to kill everything in your way. It’s worth noting here that talking about Doom’s sound can be made even more subjective than you’d imagine. Being MIDI-focussed meant the sounds of Doom were subject to what soundcard the player was using in their system. Many source ports give you the option to emulate a plethora of them which give unique sound profiles, and finding the “best” one is a matter of preference. The intention is all the same though, and despite the overt inspiration coming from the heavy metal world – which is all great stuff – Bobby Prince’s Doom soundtrack also dips into areas of dark ambient, not too dissimilar to Trent Reznor’s score for Quake. I love these tunes especially. They add a lot to some levels, slowing the game down with the implication of a furtive approach being more suitable. Doom isn’t a stealth game by any means, but levels with these tracks feel oddly sedate in comparison to the loud brutality found in the majority of the game, and I can vividly remember scouring levels for puzzles more intently while these songs played too, conditioned like a dog.

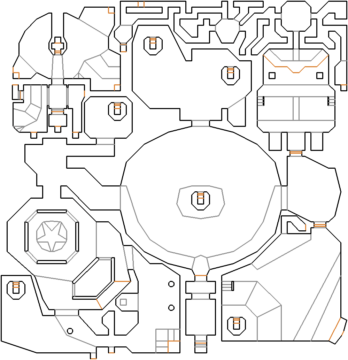

The levels: You’re a speedy boy. You’ve got big fuck off weapons. The opponent’s fit into a distinguishable, concise pool. The music makes you want to headbutt all of them. But the levels are where it all comes together. This right here is what made me realise I’d been playing trite throughout my whole juvenile life, a perfect blend of tight corridors leading to open battlegrounds, spread wide with secrets and hidden passages which all come together on each other and have you backtrack is the most beautiful fashion. I’m getting teary just writing about this, guys, it truly is something special. This image right here is certainly circlejerking, hyperbolic Reddit bait, but there is a grain of truth in it. Doom lacks story, and levels are nothing more than gauntlets with a finish line (which goes some way to explain the fervent speedrunning community). Most levels have you find keys to unlock doors which consequently lead you to the end, but id Software have made it feel like you’re doing so much more than that. Each room you walk into is a new challenge; enemies are strewn across them from all manner of heights and lumped in at differing quantities, while environmental hazards like lava and poison also vie for your blood. While in retrospect Doom errs on the side of ease (on standard difficulty anyway), the core focus on scavenging and conserving ammo always rings true, and judging what weapons to use in combat encounters is just as thrilling as executing the stratagem itself. It goes a long way – the focus on conservation that is – to explaining why the levels are built the way they are, and it gives you just that much more motivation to head out and explore them.

An example map from E3M7, courtesy doom.fandom.com

It can’t be overstated how varied they are either. Knee-Deep in the Dead may be the perfect episode, but The Shores of Hell and Inferno put up one hell of a fight for that honour too. Inferno specifically utilises open areas more frequently than the other two and generally experiments a bit more too. The former two episodes are more “traditional” Doom, marked by winding levels whereby you need to navigate sprawling map designs and dodge terrible terrain to reach the end. The game’s secrets aren’t silly nothings like those found in Wolfenstein 3D either. They actually had thought put into them, or in a more forgiving light, id Tech 1 facilitated secrets which weren’t just bashing your head against the wall, spotting imperfect wall textures or flipping switches which activate something somewhere else run amok, it’s simply fun finding them all.

Except Thy Flesh Consumed. I say I’m reviewing The Ultimate Doom, but up until now the review has been of Doom. The game which claims to be the superlative experience is actually just the original three episodes plus a bonus episode released a year after the sequel which – get this – sucks! Why does this exist, for one? It came after Doom 2, for fuck’s sake, who wanted this? Thy Flesh Consumed can be summarised as a catastrophe of bizzare level design filled with unfair hazards, woeful enemy placements and a morsel amount of ammo. Using the chainsaw is fun when you know your limits. Using the chainsaw because the game gives you no ammo against a million barons of hell isn’t. The first two missions are definitely the biggest offenders; after those the game definitely calms down on the bullshit difficulty front. Even still though, I couldn’t help but be bored during the entirety of the episode. The levels just aren’t well designed. They make no sense and visually just retread the steps made by the original three episodes. Stranger still, they were all designed by John Romero, the industry legend which designed the whole of Knee-Deep in the Dead. Perhaps he wasn’t what made Doom great afterall.

A paragraph is all I can muster for Thy Flesh Consumed. Quite frankly, it doesn’t deserve my time, both in writing and in playing. Doom – the original three episodes – is an undeniable masterpiece. It’s a game that not only survived the harshness of the banal 2010’s modern military shooter craze, but it’s one which came out looking even stronger, spawning sequels which the industry was in dying need of. If anything, Doom 2016 and Doom Eternal’s booming success only reinforced my belief that the formula Doom created is a winning one, and still almost 30 years later continues to lead the pack.